Mastication and Eating Rate: How the Mouth Modulates Carbohydrate Digestion and the Metabolic Impact of the Same Meal.

The simple act of chewing may be one of the most overlooked yet powerful tools in metabolic health. Eating speed is not merely a behavioral quirk—it is a robust predictor of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risk. Fast eaters are twice as likely to develop obesity and metabolic syndrome compared to slow eaters, independent of total caloric intake.[1-4] In fact, the same meal consumed at different speeds produces dramatically different metabolic responses, with fast eating associated with higher postprandial glucose peaks, elevated insulin levels, and impaired satiety signaling.[5-6] This phenomenon begins not in the stomach, but in the mouth, where the mechanical and enzymatic processes of mastication set the stage for the entire digestive cascade.

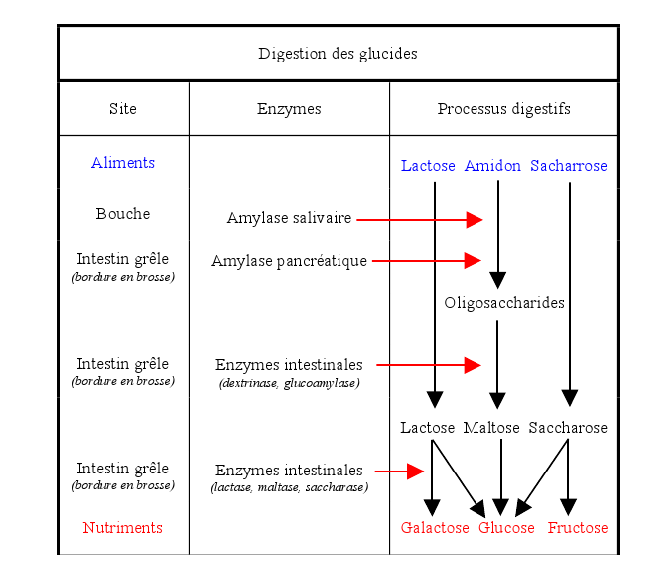

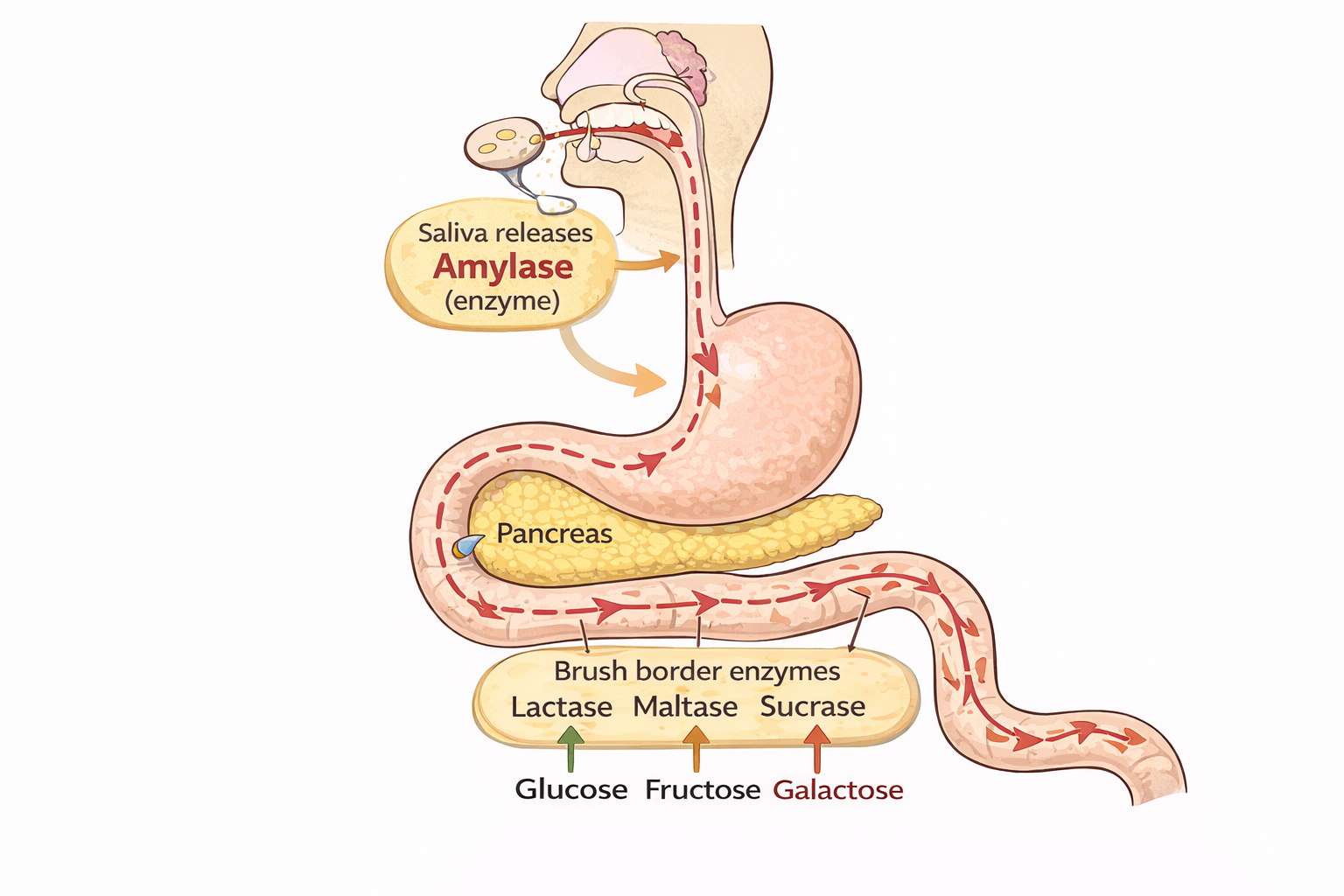

Carbohydrate digestion begins in the mouth, where mastication mixes food with saliva containing salivary α-amylase, initiating the hydrolysis of starch into smaller oligosaccharides and maltose. This oral phase is significant: salivary amylase can hydrolyze up to 80% of starch in bread before gastric inactivation, demonstrating a substantial contribution to early carbohydrate breakdown.[7-9] In contrast, the stomach does not contribute to carbohydrate digestion, as its acidic environment rapidly inactivates salivary amylase.[10]

In the small intestine, pancreatic amylase continues starch hydrolysis, producing disaccharides and oligosaccharides. These are further cleaved by brush border enzymes—lactase, maltase, and sucrase—into absorbable monosaccharides: glucose, fructose, and galactose.[10]

Chewing speed and thoroughness modulate the efficiency of oral carbohydrate digestion. Rapid eating reduces saliva contact time, limiting salivary amylase action and resulting in larger bolus particles, which can accelerate glucose absorption and produce higher postprandial glycemic peaks.[6][11] Conversely, slower, more thorough chewing increases saliva uptake, enhances early starch hydrolysis, and promotes gradual glucose absorption, which is associated with improved satiety and more favorable activation of satiety hormones such as leptin and cholecystokinin.[5][12] This can lead to better metabolic control and reduced appetite. Increasing chewing from 15 to 40 cycles per bite significantly reduces hunger, desire to eat, and postprandial glucose excursions while increasing insulin and satiety hormone secretion.[12-13]

Importantly, the same caloric intake can yield different metabolic responses depending on mastication. Increased chewing cycles and slower eating rates are linked to altered postprandial glucose, insulin, and satiety hormone profiles, independent of total caloric content.[5-6][12] The glycemic index of rice, for example, increases from 68 to 88 when chewing time is doubled from 15 to 30 cycles per bite, demonstrating that oral processing behavior directly influences glycemic response.[14] Thus, oral processing behavior is a modifiable factor influencing glycemic control and satiety, with clinical implications for metabolic health.

Written by Dr Michael Roger

Family Medicine Consultant

copyright Dr Michael Roger.

REFERENCES

1.Eating Speed, Eating Frequency, and Their Relationships With Diet Quality, Adiposity, and Metabolic Syndrome, or Its Components.Nutrients. 2021. Garcidueñas-Fimbres TE, Paz-Graniel I, Nishi SK, Salas-Salvadó J, Babio N.

2.Association Between Self-Reported Eating Speed and Metabolic Syndrome in a Beijing Adult Population: A Cross-Sectional Study.BMC Public Health. 2018. Tao L, Yang K, Huang F, et al.

3.Association Between Self-Reported Eating Rate, Energy Intake, and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in a Multi-Ethnic Asian Population.Nutrients. 2020. Teo PS, van Dam RM, Whitton C, Tan LWL, Forde CG.

4.Eating Speed and Risk of Metabolic Syndrome Among Japanese Workers: The Furukawa Nutrition and Health Study.Nutrition. 2020. Nanri A, Miyaji N, Kochi T, et al.

5.Increased Oral Processing and a Slower Eating Rate Increase Glycaemic, Insulin and Satiety Responses to a Mixed Meal Tolerance Test.European Journal of Nutrition. 2021. Goh AT, Choy JYM, Chua XH, et al.

6.Eating Fast Has a Significant Impact on Glycemic Excursion in Healthy Women: Randomized Controlled Cross-Over Trial.Nutrients. 2020. Saito Y, Kajiyama S, Nitta A, et al.

7.Oro-Gastro-Intestinal Digestion of Starch in White Bread, Wheat-Based and Gluten-Free Pasta: Unveiling the Contribution of Human Salivary Α-Amylase.Food Chemistry. 2019. Freitas D, Le Feunteun S.

8.Chewing Bread: Impact on Alpha-Amylase Secretion and Oral Digestion.Food & Function. 2017. Joubert M, Septier C, Brignot H, et al.

9.Salivary Amylase: Digestion and Metabolic Syndrome.Current Diabetes Reports. 2016. Peyrot des Gachons C, Breslin PA.

10.Non-Pancreatic Digestive Enzymes.Biomolecules. 2025. Borowitz D.

11.Assessment of the Influence of Chewing Pattern on Glucose Homeostasis Through Linear Regression Model.Nutrition. 2024. Riente A, Abeltino A, Bianchetti G, et al.

12.Increasing the Number of Masticatory Cycles Is Associated With Reduced Appetite and Altered Postprandial Plasma Concentrations of Gut Hormones, Insulin and Glucose.The British Journal of Nutrition. 2013. Zhu Y, Hsu WH, Hollis JH.

13.Morning Mastication Enhances Postprandial Glucose Metabolism in Healthy Young Subjects.The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2019. Sato A, Ohtsuka Y, Yamanaka Y.

14.Mastication Effects on the Glycaemic Index: Impact on Variability and Practical Implications.European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2014. Ranawana V, Leow MK, Henry CJ.